This zine represents the messages young people wanted to share with decision-makers and educators, to help you make responsible AI a reality in education.

1: Representation →

2: Personalisation →

3: Labour →

5: Agency & rights →

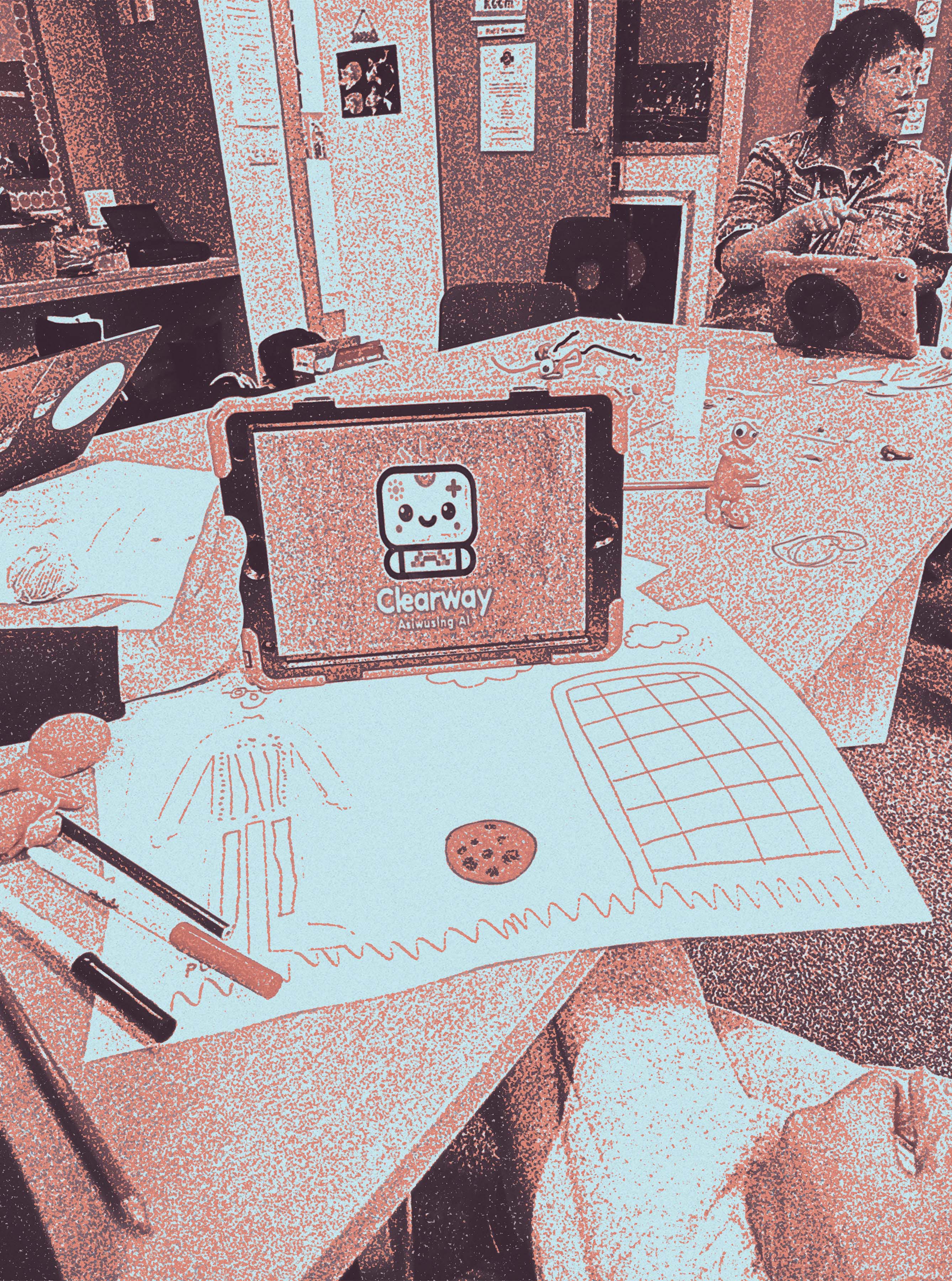

In June 2024, young people at three secondary schools took part in workshops on the topic of the future of responsible artificial intelligence in education.

This work was part of a larger research project on the emerging context of generative AI (GenAI) tools and their implications for education, now and in the future.

This zine is one outcome from these workshops, and it represents the messages young people wanted to share with decision-makers and educators, to urge you to make Responsible AI a reality in education.

The young people were creative, thoughtful and imaginative – these materials express their hopes, fears, and personal meaning-making with and about AI. We encourage you to see their images and words as an important act of AI literacy, expressed through creativity, collaboration and reflection.

For the most part, young people are providing you with questions, not answers. We learned and had our assumptions challenged by their work. Please take what they have offered here as a provocation, a confrontation and an opportunity to think expansively about your own values and hopes for education.

context of the research

The workshops involved 22 young people at three different sites – a secondary school in Edinburgh (participant ages 16-17), another in Norfolk (ages 17-18) and an additional needs school in Edinburgh (ages 13-16).

At each school, artist-practitioners facilitated the workshops, which incorporated imaginative, exploratory and speculative activities.

The facilitators of the additional support needs (ASN) workshops were chosen for their experience in conducting creative and participatory work with young people with ASN.

GenAI is being widely adopted in formal and informal education settings in the UK, either boldly or furtively, but research is showing it is happening. For this to be a responsible practice, issues around discrimination, inclusion, and fairness urgently need to be addressed.

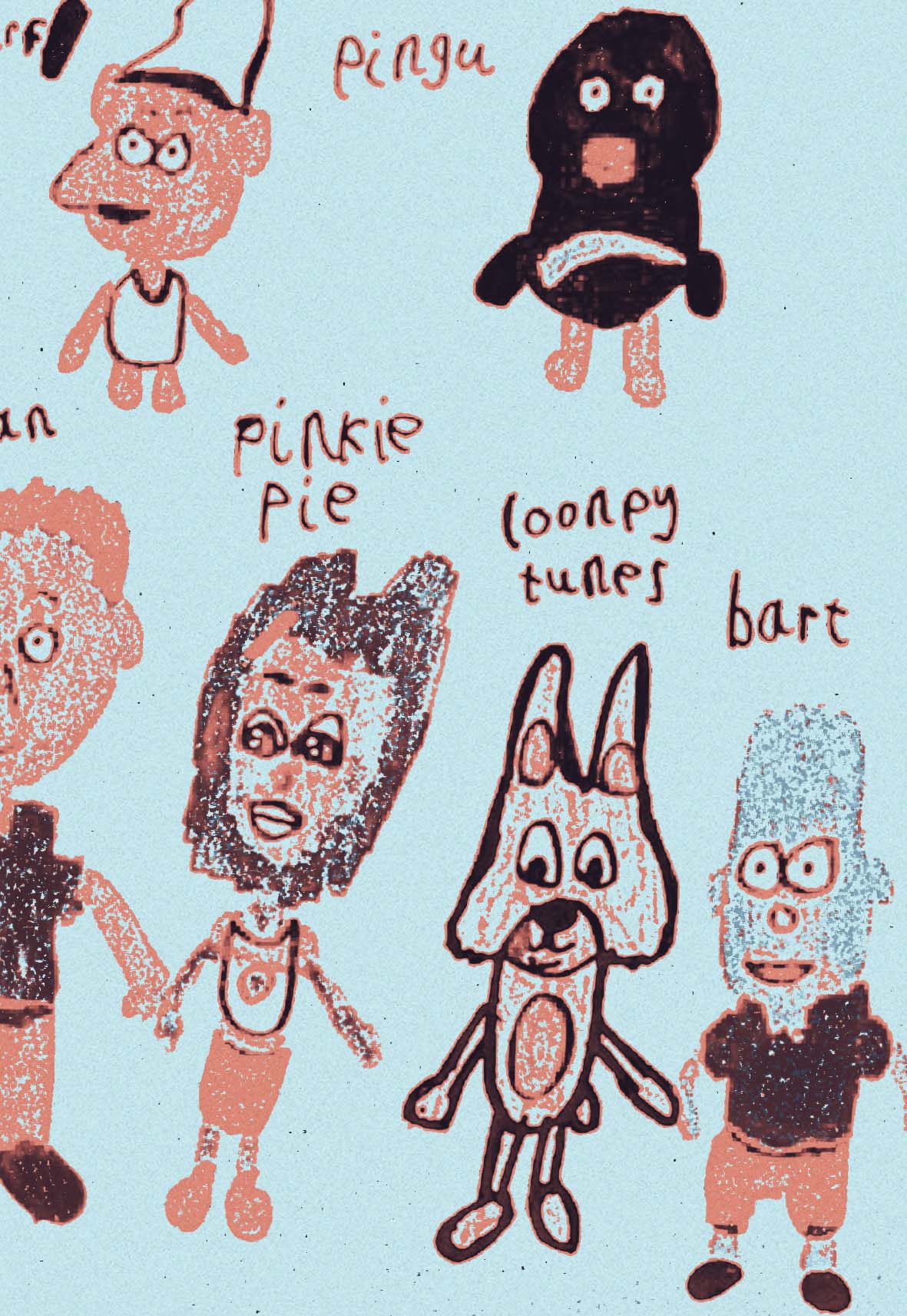

representation of self and interests

Young people explored who is represented in AI systems. There were many positive moments where AI helped them express and communicate about themselves.

One envisioned Responsible AI as being fair and unbiased if it ‘doesn’t judge the user’. She created a vibrant image of herself as a peacock in a silk suit with a galaxy print, flying through space and time.

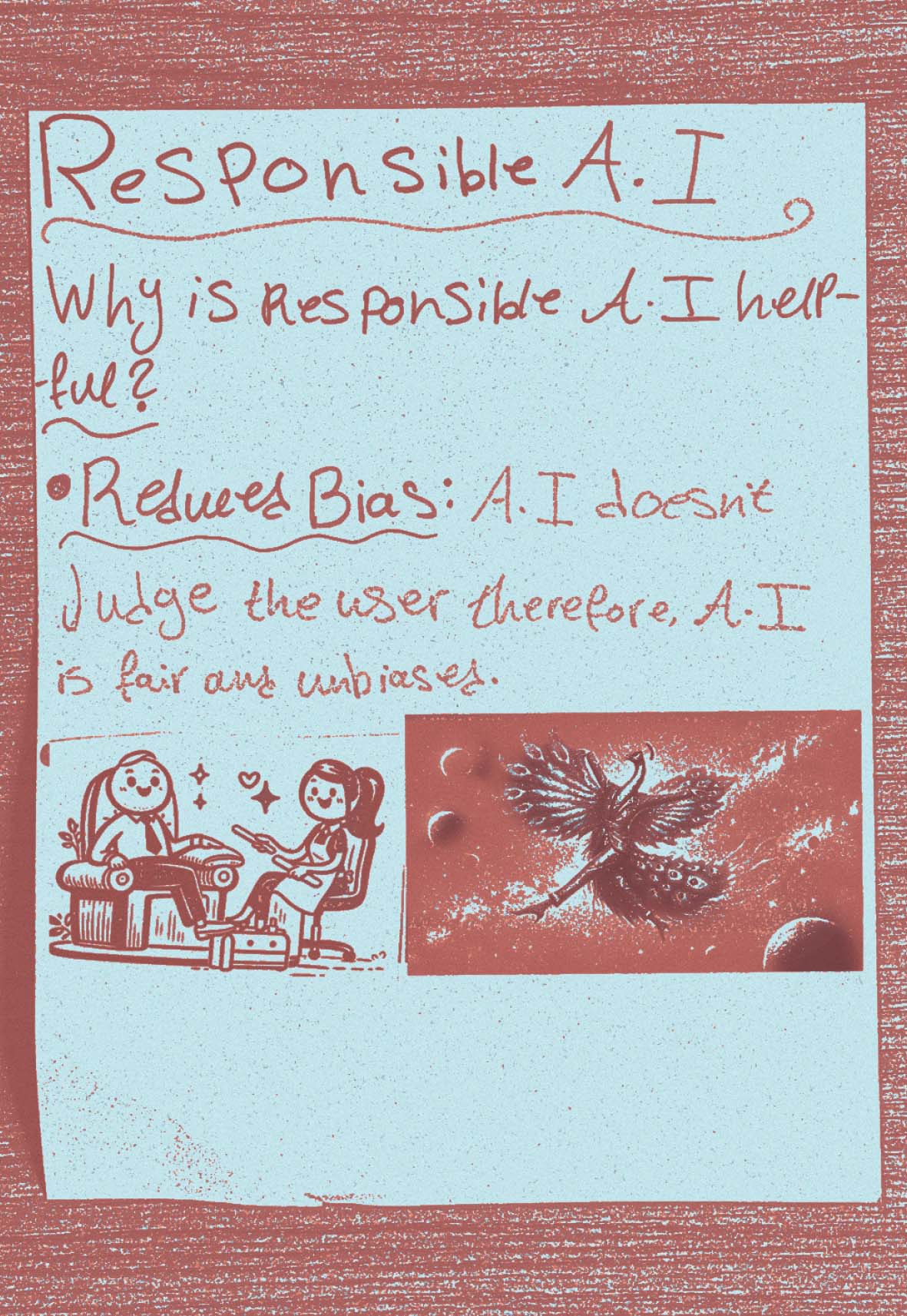

Another used GenAI to represent himself as a footballer, building a story of going to a football match and scoring a goal. Here the GenAI tools reflected and expressed interests and aspirations, supporting creative engagement. Young people were able to play with ideas of who they are and how they’re seen.

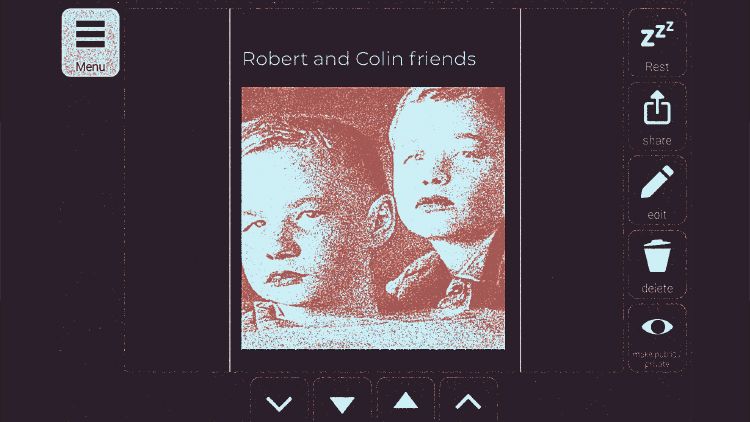

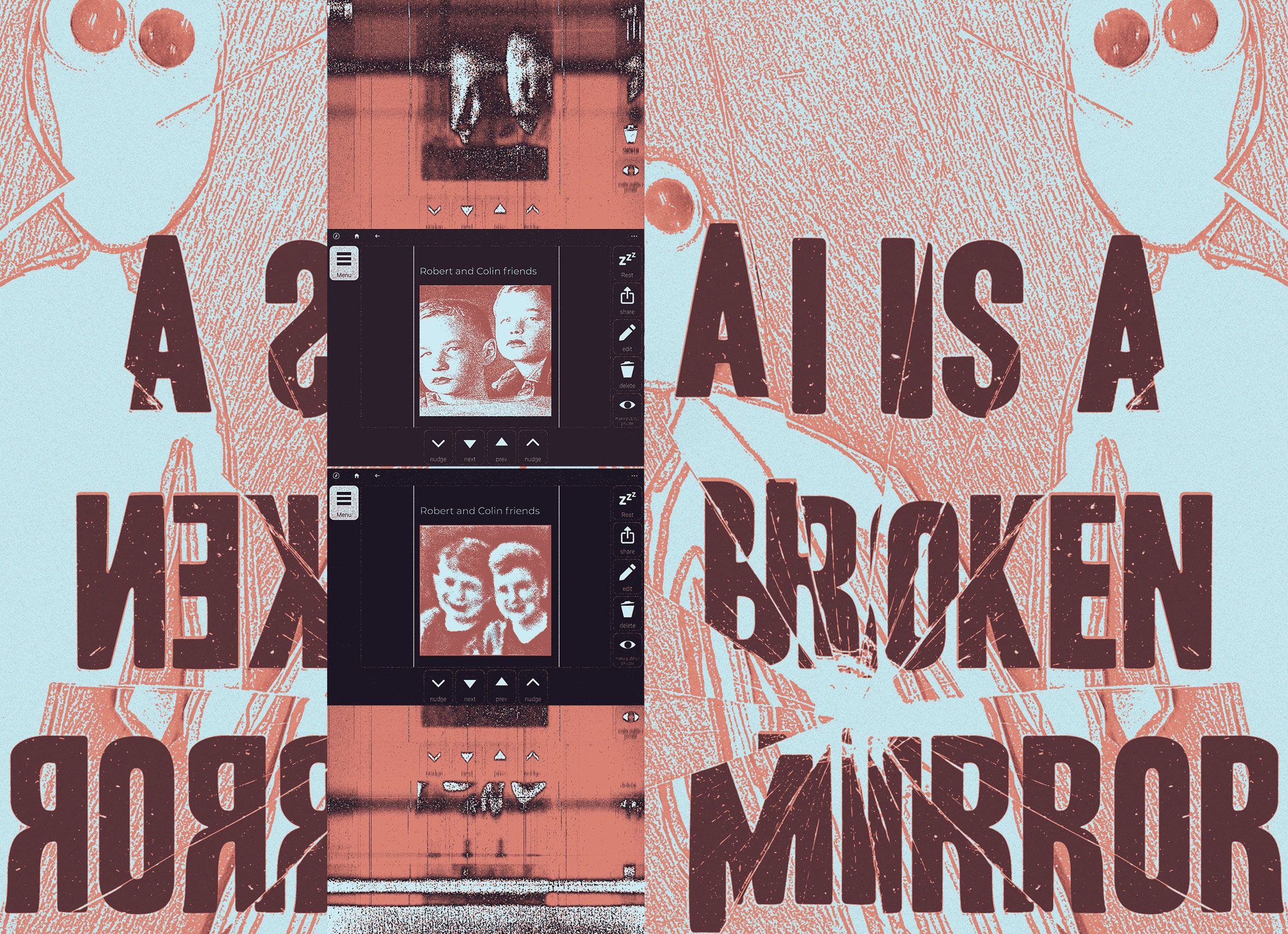

However, young people also discovered GenAI’s pervasive bias. One minimally-verbal young person in the ASN school wished to use AI to create an image of himself and his best friend. He wrote ‘Robert and Colin smiling’ as a prompt. GenAI came back with an image showing two white children, which did not fit with Robert’s race, but did with Colin’s. He shook his head and clicked ‘recreate’ – again and again it produced a similar image of two white children.

Robert appeared disappointed and said ‘No... Colin and Colin’. Robert’s interest in the activity and in the technology disappeared. GenAI is white by default and this is exclusionary, particularly in additional needs contexts where the young person may not know how to (or want to) prompt the system about their race, or any other characteristic.

Sometimes, GenAI was able to support playful iteration of participants’ own ideas and existing interests. Colin hand-drew a storyboard about driving to a football match in his car and scoring a goal and then brought elements of it to life through GenAI. He generated multiple variations of what his red car would look like, each iteration bringing him joy.

At the same time, the hand-made zine creations are brimming with expression and personality. Could these images be enhanced by GenAI? Perhaps – but do we need to?

inaccessibility prevails

Even when using a GenAI program designed for additional needs, usability and accessibility issues emerged. For example, the program used predictive modelling in ways that suggested unhelpful, wrong or even alarming word choices. When Colin was searching for an icon for ‘kick’ (the ball), it consistently suggested only ‘kill’ or ‘kiss’, forcing ideas which were not wanted and which dampened his enthusiasm.

The design of accessible programs can improve access in some ways (for example offering icons in place of written text) while creating barriers in others (requiring multiple clicks to input a single prompt). If GenAI has educational value, it should be accessible in additional needs contexts and young people should not be excluded from its use due to design barriers.

Beyond the design of specific interfaces, assumptions of verbal and language ability are built into GenAI tools and their metaphors. The message AI development companies give is that “educational AI is for everyone” and can level the playing field.

However, it’s only for everyone if no-one deviates from the norm.

For example, Robert created a drawing of himself and his friend, both with no mouths. This was a common theme in his drawings and may express something of his understanding of being minimally-verbal. When he tried to mirror his drawings by prompting the GenAI, he was increasingly frustrated at the images which were returned, all with mouths, all smiling.

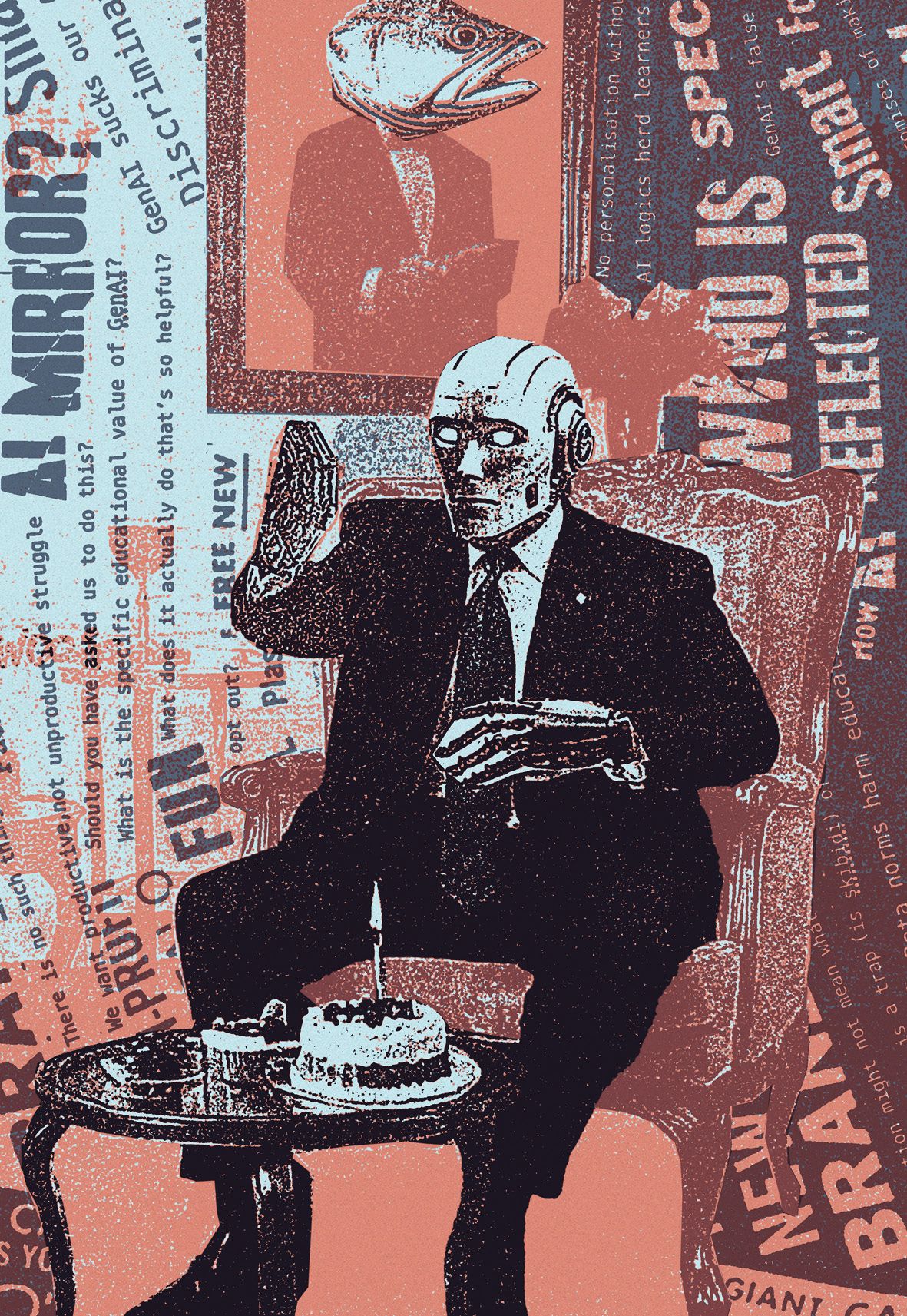

Through young people’s work, GenAI served to amplify stereotypes and biases. At a technical level, these are systems for pattern seeking at scale – searching for the most common patterns and predicting what comes next.

GenAI emerged here as not just a mirror, but a broken mirror, one in which not everyone is reflected, accurately or at all. Can we responsibly introduce such systems into our schools? How do they need to change to better represent all young people, not just a few? ◆

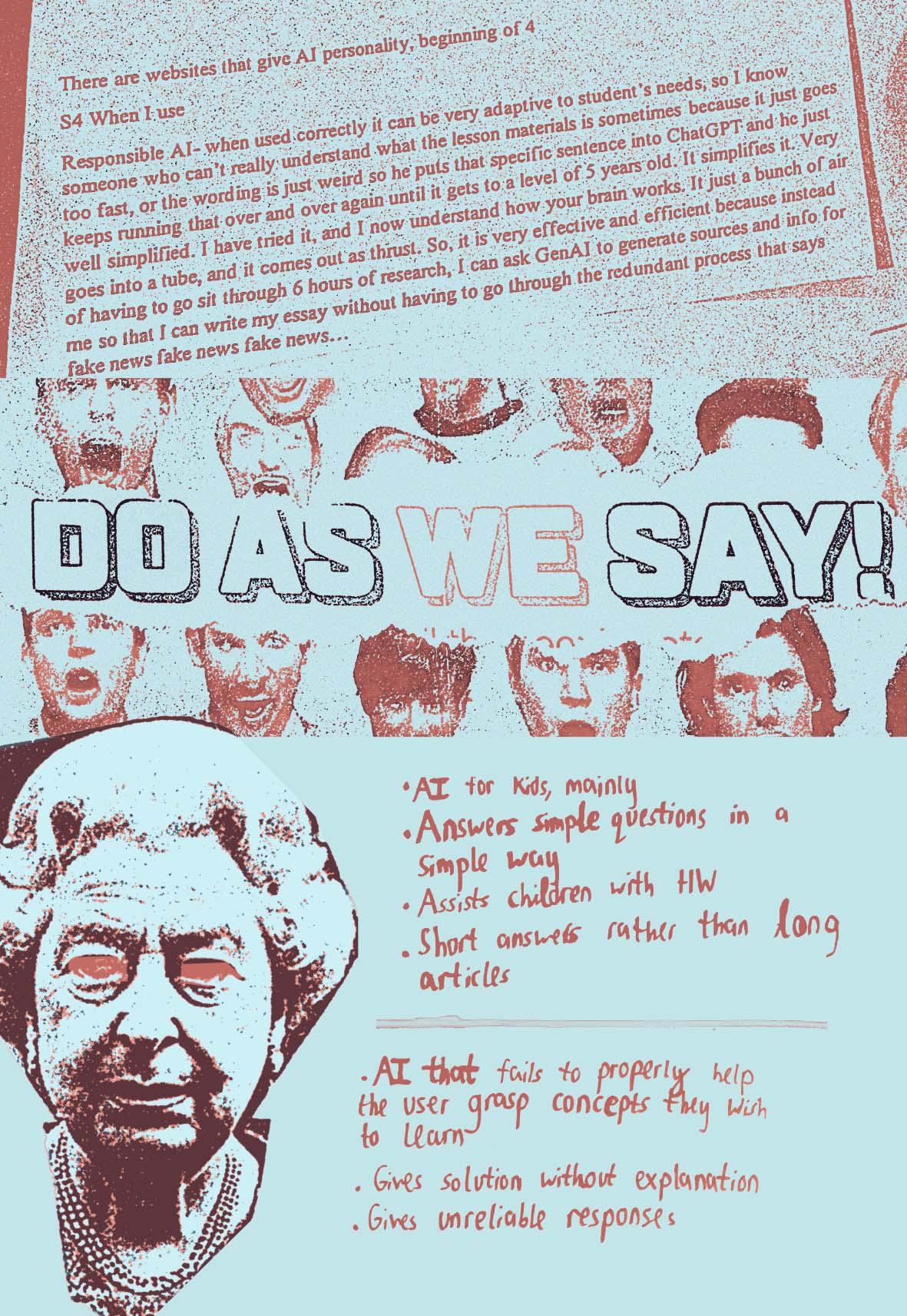

AI claims to offer smarter, personalised, bespoke opportunities for learning for different kinds of learners.

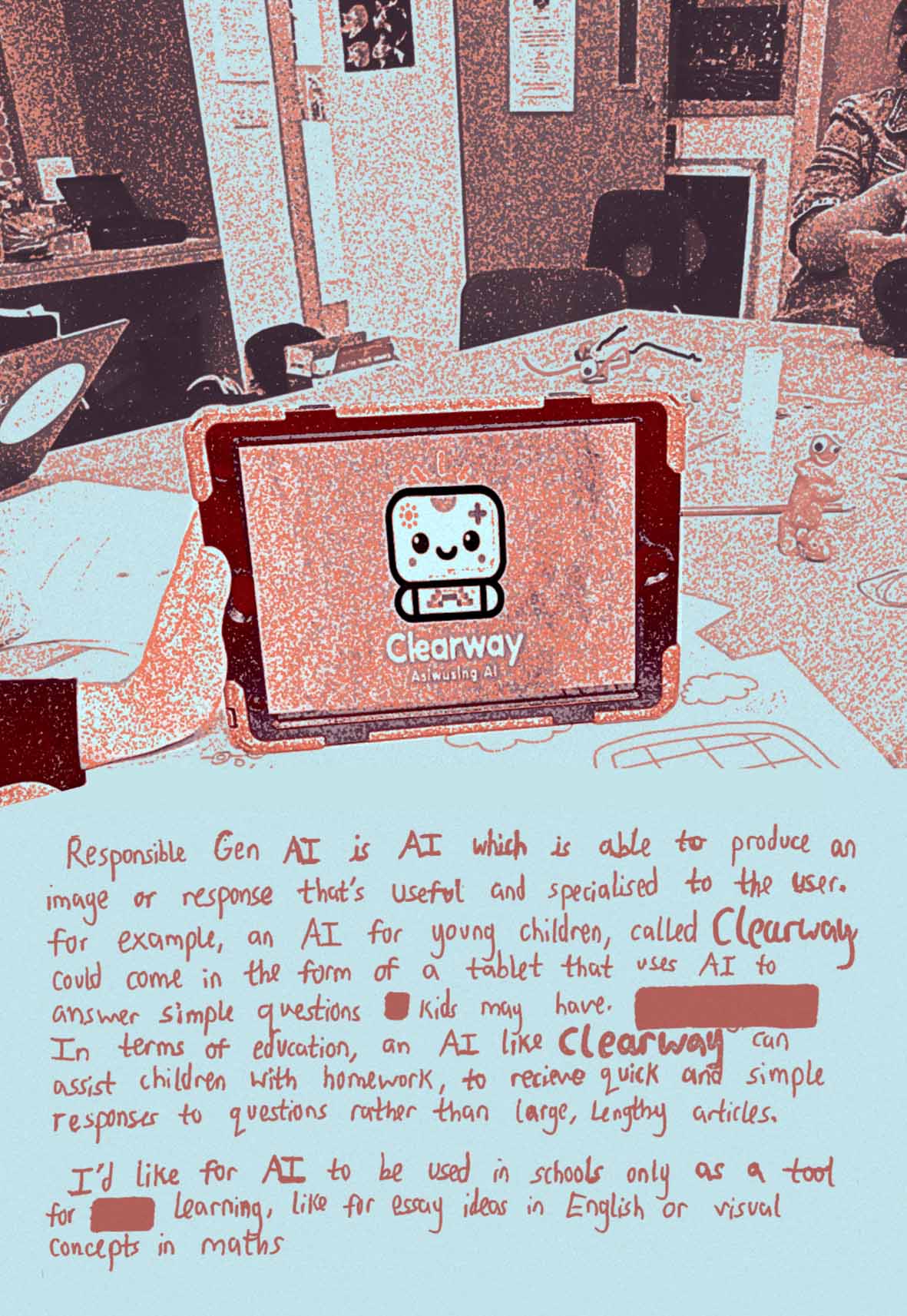

Young people are excited by the promises of adaptive technology and access to limitless resources. AI, when used responsibly, is believed to act as a ‘second brain’ and as an ‘ally’. It’s seen as helping us use time more efficiently while delivering knowledge in an age-appropriate, tailored way.

But does AI deliver on these personalisation claims? Or does it largely deliver standardised experiences, offering knowledge and experiences that are drawn from the middle and for ‘the norm’? It seems that AI can often fall short of

the high expectations of a personalised learning experience.

AI can simplify knowledge for younger users. But are such explanations good enough?

If AI offers ‘simple’ solutions without adequate explanations, or obscures deeper understandings, or is just unreliable, it becomes irresponsible.

GenAI cannot reflect the context of the learner or their specific needs (unless vast amounts of personal data have been offered) and young people discussed examples from the media of AI tools suggesting harmful/destructive or inappropriate solutions – such as recommending the sticking of fingers into an electrical socket to reduce boredom.

At other times AI’s offer clashes with young people’s own understandings and knowledge base – for example, when images of historical figures like Churchill or Queen Elizabeth II appear inaccurate or fake. They wonder: does knowledge get relegated to ‘matters of opinion’? They worry about censorship of personal knowledge and beliefs.

Using AI can also exacerbate a sense of ‘exclusion’ rather than personalisation. What is the price of truly personalised interactions? Do you need ‘premium’ packages, and how much private data needs to be offered? What are the trade-offs that you are willing to live with? ◆

Irresponsible AI - solutions, not explanations

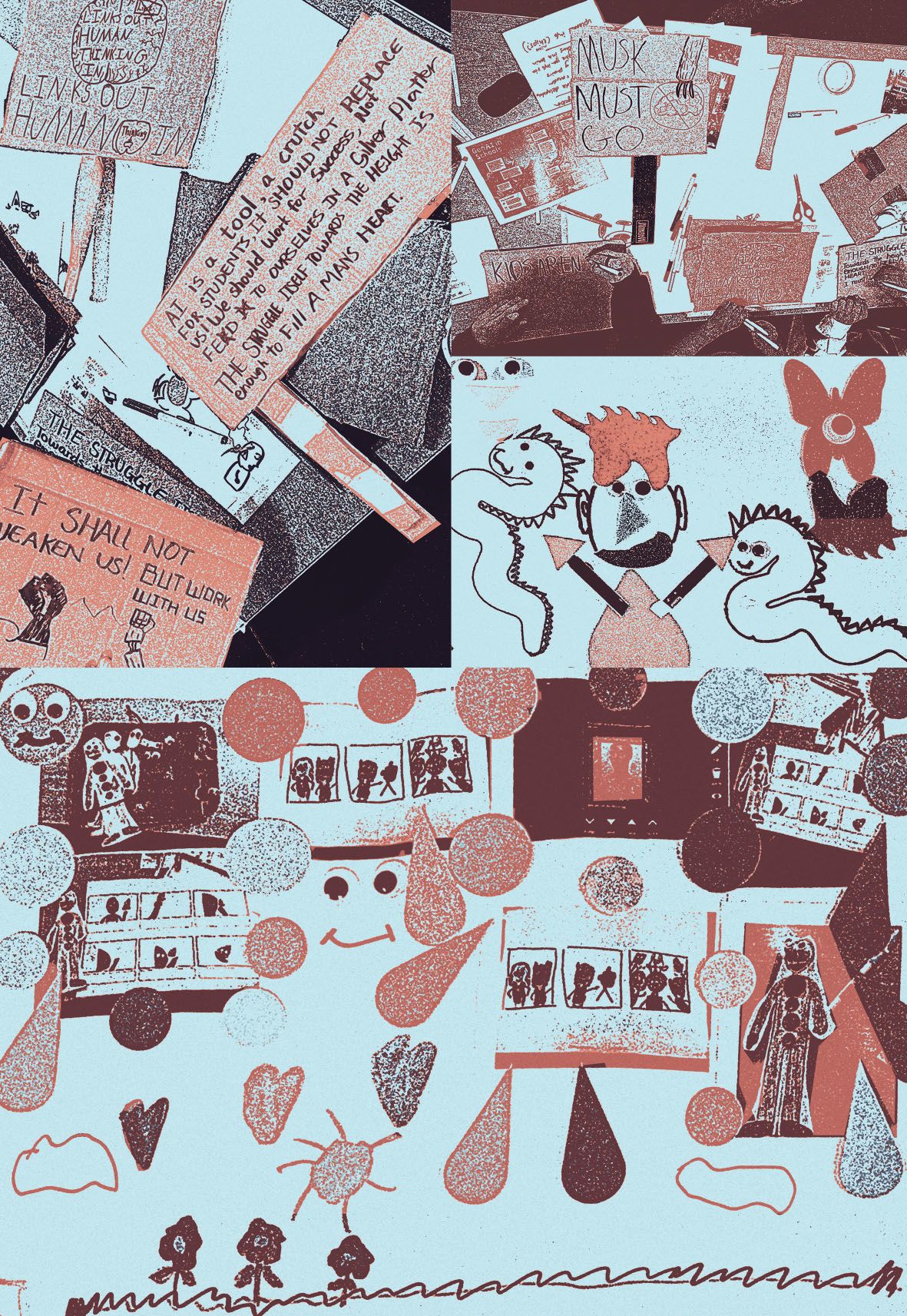

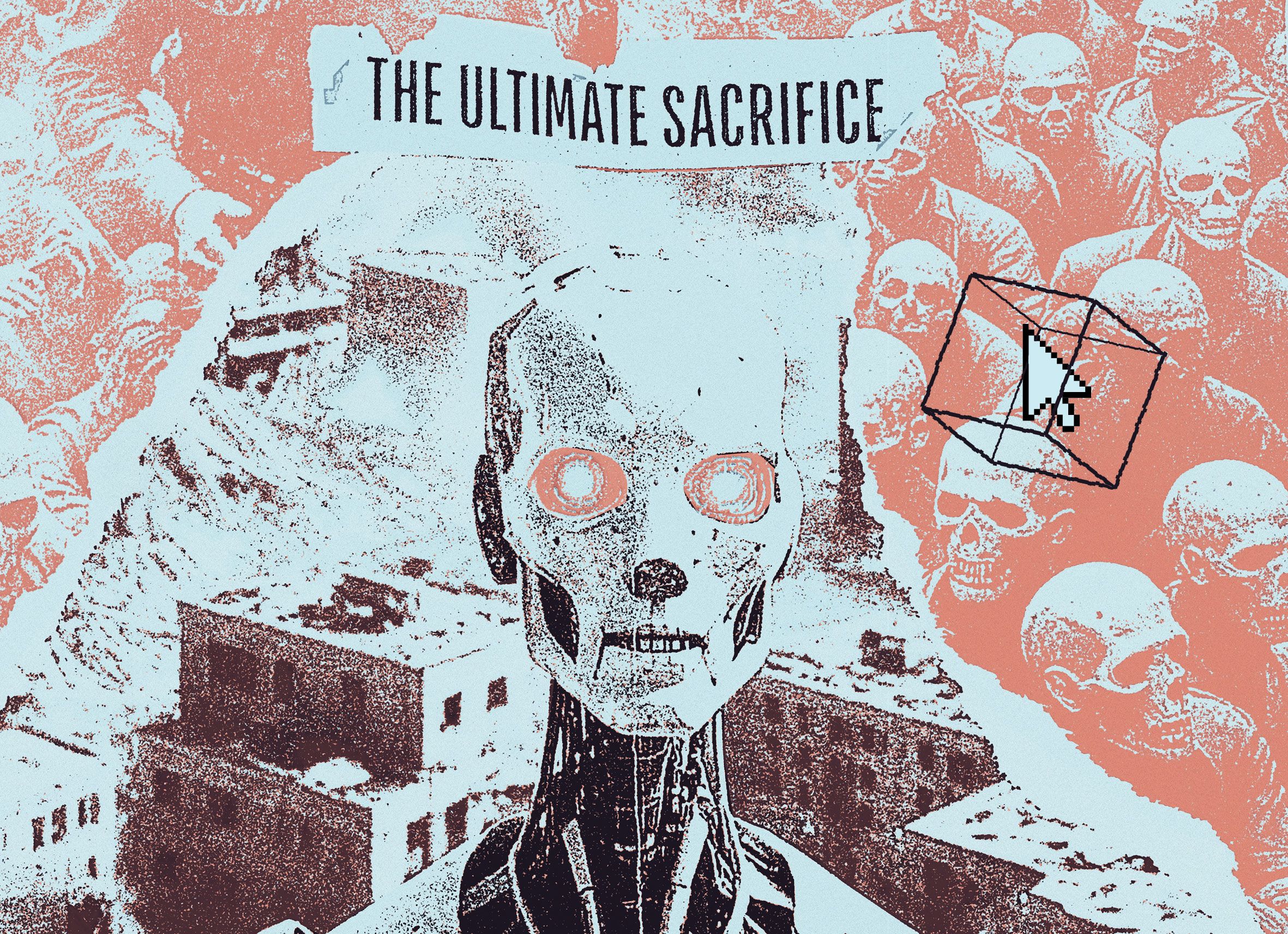

Discussions in the workshops often came back around to the idea of labour(s), including the ways in which AI refused to show its work: not showing sources, not explaining the seemingly random logic to arrive at different results, lacking transparency. Young people explored and represented different forms of human labour (emotional, mental, temporal) that were created or lost through struggling with AI.

The struggle is real

Even though AI is sold as a way to make things easier, the reality of which labour was removed or valued by AI was less clear to young people. The image of a Sisyphean struggle came up in different ways:

- young people struggled against a stubborn AI to get what they were looking for

- a human struggle for knowledge was valued.

Rather than having things easier, young people wanted support to learn, which involves struggle and hard work. Current GenAI iterations seem to work against this desire.

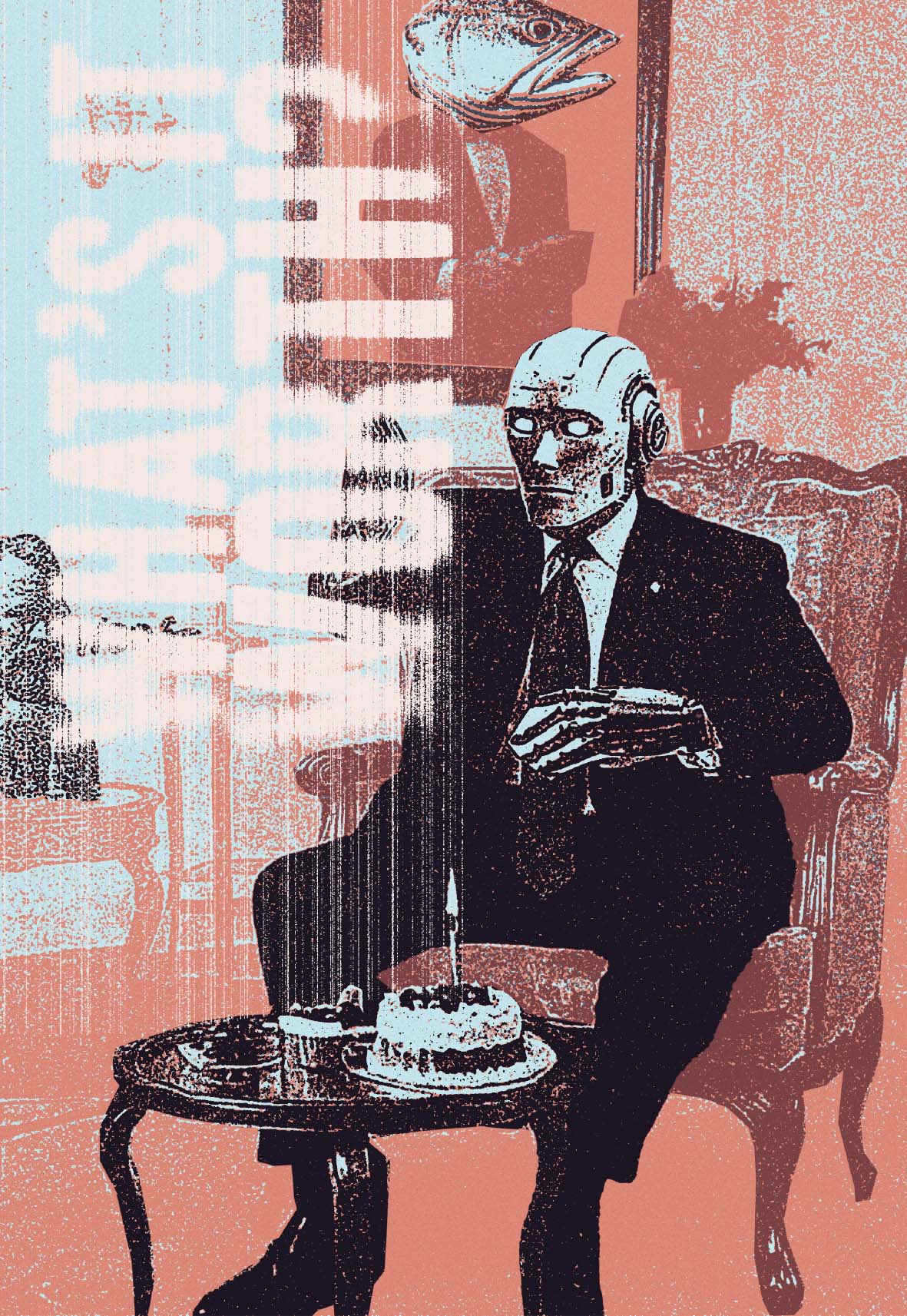

Where is the human?

Young people expressed their frustrations about the ways in which AI pretended to be a friendly human figure that was ‘working’ for them. They saw AI as an uncanny and shallow version of humanity. For example, the GenAI tool’s use of emojis more often than not deployed a version of humanity and emotion in inappropriate ways. At times AI would use words that emphasised its artificiality whilst using emojis to make the message friendlier, sending confusing messages about its labour.

The frustration of engaging with AI

Engaging with AI proved frustrating and took a lot of emotional labour from the young people. They often ended up regulating themselves for the AI, rather than feeling that AI was working for them. Throughout the workshops, young people were doing the work of trying to get AI to work for them and being met with dead ends and demands to move on from what they were interested in exploring. AI would send them to other platforms, shut down their chat, or refuse to engage with them without explanation. This was particularly acute when combined with discrimination and bias from the AI.

False promises

GenAI is increasingly pitched as a labour-saving device, but the reality was that it created new and additional forms of labour. Alongside the emotional labour of fighting to make AI produce what they wanted, there was also added labour of working through the outputs and making sense of what was given to them. This work involved multiple people, including other young people, teachers, support staff, and others. The young people saw disconnects between how AI was presented to them as a helpful ‘aid’ for learning, and the ways in which it could end up creating more problems and additional work.

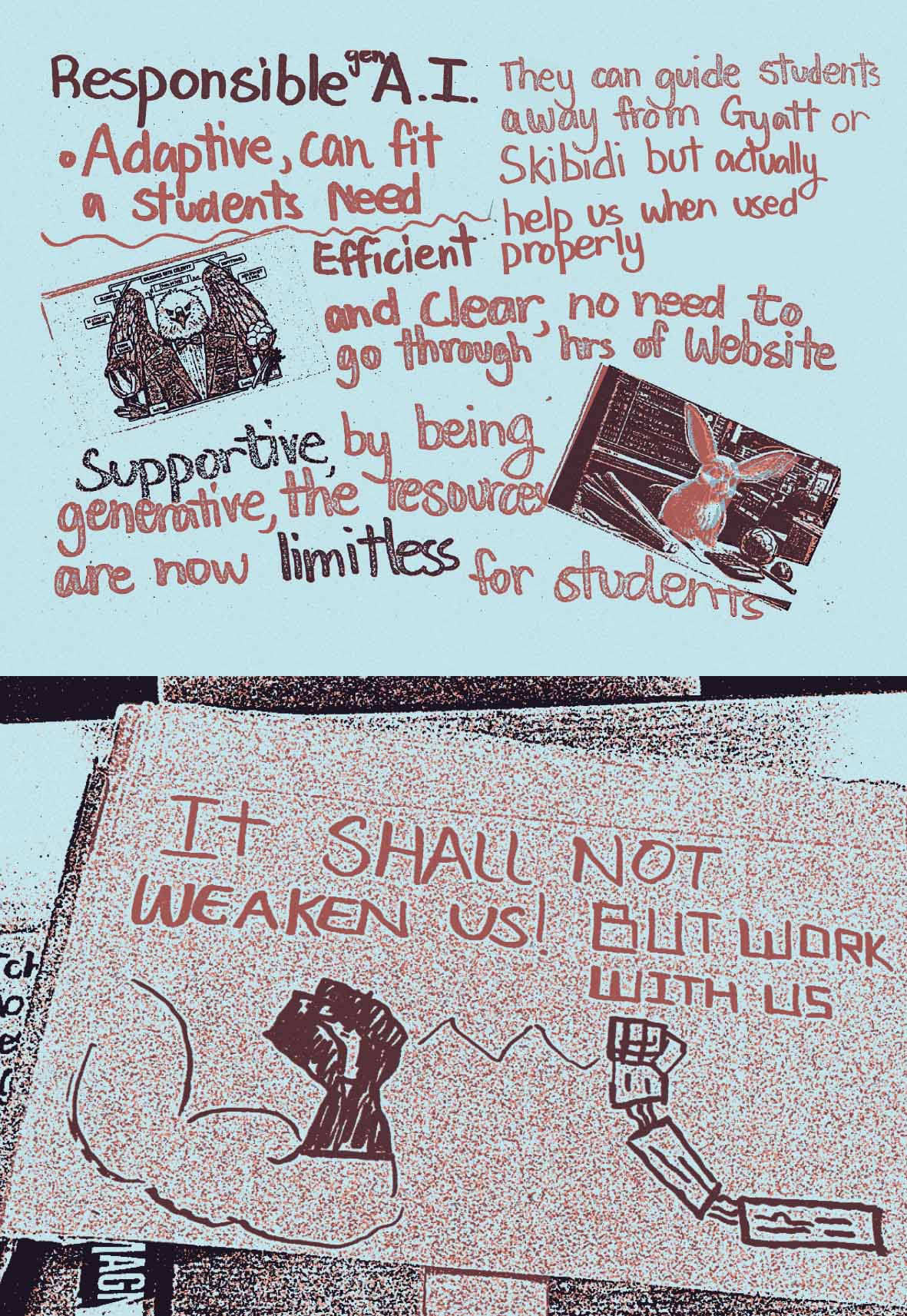

Young people’s vision of responsible AI is of AI that brings value to their own and others’ education, and reflects values they see as central to education itself.

This is not simple, because claims for the value of GenAI in education are still largely hypothetical, while the educational, environmental and other costs of GenAI are already becoming apparent. Teachers, researchers and others are also working to identify the value that GenAI brings to actual educational settings.

This vision of responsible AI highlights qualities of access, efficiency and support. However, these qualities are not yet shown to be achievable using GenAI.

The next vision focuses, instead, on the potential for GenAI to inspire learners. Inspiration, enjoyment and fun played an important part in young people’s work with GenAI and what they value in their personal engagements with it.

When GenAI tools were able to respond appropriately to the prompts given, or even exceed expectations, this sparked pleasure and a feeling of empowerment.

When they failed to do so, as they often did in our workshops, the learning costs of this kind of technology in schools were revealed: frustration, alienation and inaccuracies that hindered understanding.

Beyond those costs, young people know of others – the extractive nature of GenAI technologies – both environmentally and in terms of intellectual property – was a major concern. ◆

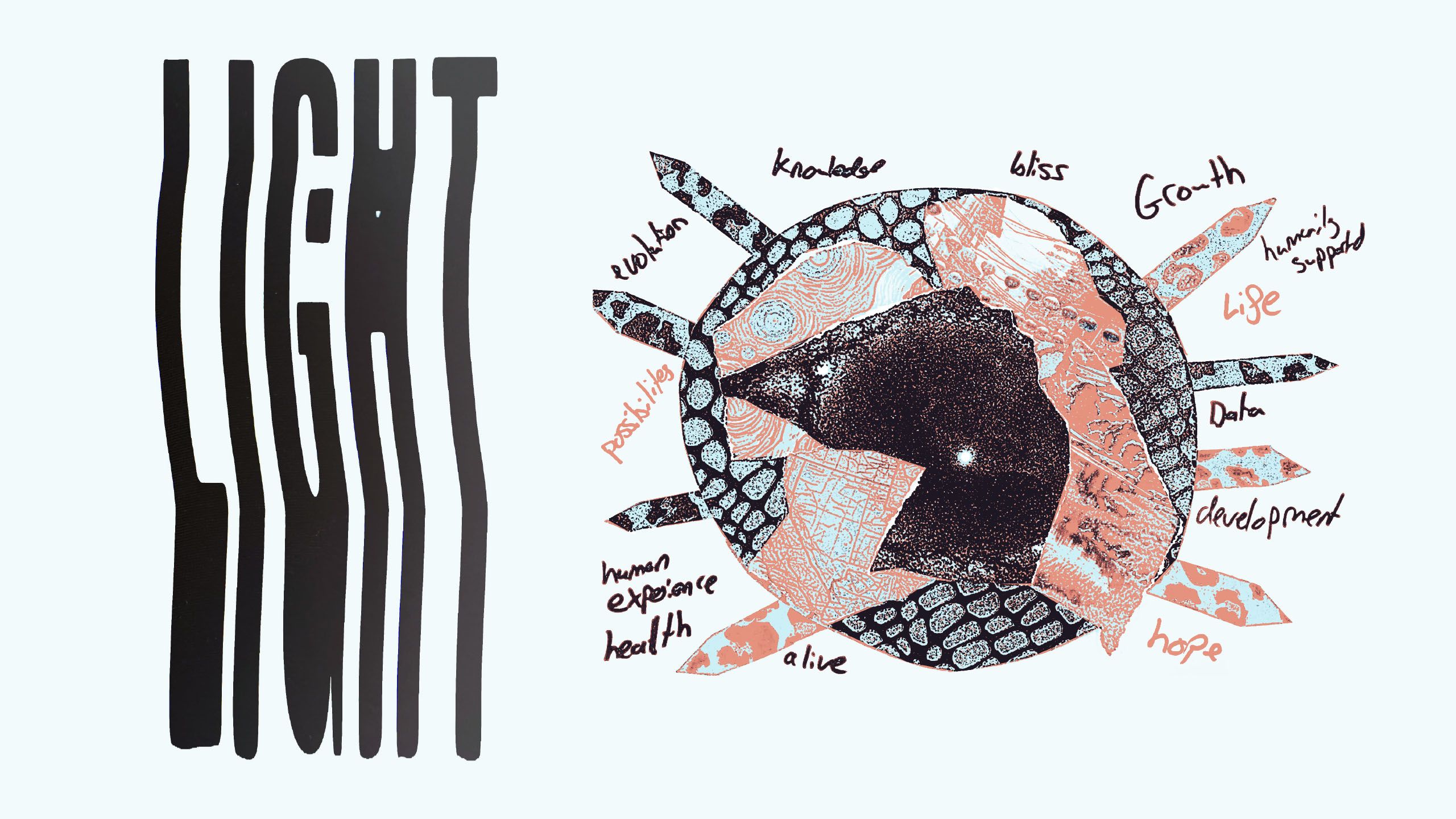

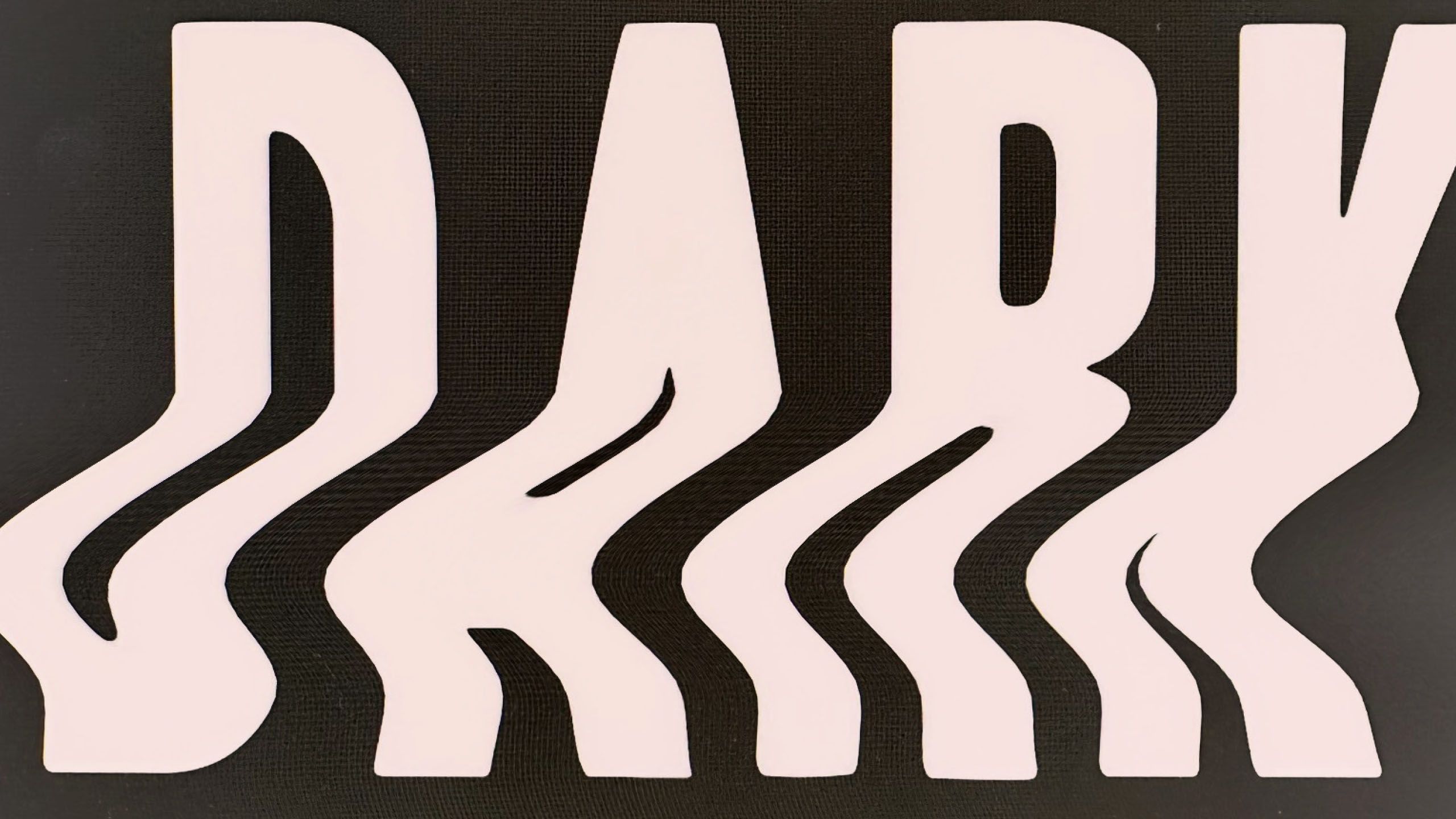

Light and dark

This pair of images investigates the light and dark side of GenAI, with knowledge, bliss and growth underpinning GenAI technology that supports human experience, health and life; and on the flip side environmental catastrophe and death the result of these same technologies.

Environmental impact

GenAI’s environmental impact because of the huge data and energy demands it makes is becoming better understood, and young people are extremely concerned about this.

The future of human creativity

An incredibly important issue for many young people, including one who opted out of using GenAI entirely in one of our workshops because of it, was about intellectual property and the use without permission of human creative outputs to feed GenAI models. The cost in jobs, and perceived threats to the future of creativity, were seen as barriers to AI being used responsibly in education. ◆

Young people want to be able to use GenAI tools without compromising their privacy, safety, or other rights.

They want their agency to be respected, and to be informed about the costs of opting in and opting out. They seek a real choice: to be informed about the benefits and risks and to be able to opt out without facing any negative consequences for their education. But they worry this will not be possible. They wonder what the alternatives are, and who is responsible if something goes wrong.

Agency means being able to consent, or refuse, and to understand what you are agreeing to.

Agency is also about being informed about benefits and risks, and what you will miss if you opt out. Responsible AI developments for education must include ensuring young people know about their rights and can exercise them, with support from teachers, who will play a critical role in helping them understand and navigate consent. This is especially the case for students with additional needs.

Young people highlighted many unknowns regarding the consequences of using or not using GenAI.

They wonder if they can trust the tech companies, when they see so many examples of unsolicited ads, bias, censorship and other negative consequences of technology. They worry about harms and risks that are not yet known. ◆

Young people care about responsible AI, but they cannot by themselves make it a reality. They have questions for you and they need to be answered. How AI is implemented (or not) into their education is your responsibility too, and at the moment young people do not think this is being done as well as it could. What are you going to do about it?

Provocations for Education Leaders

Measuring value

- What is GenAI adding? Who really needs it, and what for?

- How can we weigh up costs and benefits of GenAI in specific contexts?

- How can robust professional decision-making about when and how to use AI be supported?

- Do we know the full extent of the environmental costs of using AI? What is the right response?

- How can we balance AI’s potential to foster enjoyment and inspiration with its potential to cause frustration and alienation?

- What needs to improve, and how can I get involved to improve it?

Assumptions & Expectations

- How can we be more conscious of our expectations of AI and the limitations of AI?

- Am I already using or affected by AI without knowing it? Where and how is automation and AI appearing in my professional life?

- Are we taking into account that images we see every day are increasingly modified by AI? How can we tell? Can we always tell? How should that inform our opinion of what is happening in the world?

- Where is my existing knowledge of GenAI coming from? How can I tell what is actually possible, what is hype, and what is potentially harmful?

Personalisation & Inclusion

- What do we mean by personalisation in education, and is this it? How can we better evaluate claims of adaptive or personalised technology?

- Is AI’s version of personalisation truly adaptive? Whose experiences are included and excluded?

- How do the assumptions of verbal and language ability in AI tools exclude certain groups? Who might be harmed, and how?

- What emotional costs arise when young people feel misrepresented or excluded by AI outputs?

- Is this emotional labour recognised and addressed by educators, or is it overlooked?

Knowledge & Rights

- How can young people be empowered to critically engage with AI systems, know their data rights, and meaningfully object if they have ethical concerns or their rights are at risk?

- Who is responsible for ensuring young people understand how their rights might be impacted when they use GenAI tools in school, or if GenAI tools are being used to make decisions about them?

- What information should schools give to young people and families about how GenAI tools are being used? What should happen when questions and challenges are raised?

- What are the potential consequences for schools, teachers, families or young people of opting out of some AI futures in education?

This zine was created as part of a scoping project funded by the AHRC Bridging Responsible AI Divides (BRAID) programme.

The project, ‘Towards Embedding Responsible AI in the School System’, ran from February-October 2024. More information about the project is here: https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/youngpeopleandai/. Members of the research team involved in developing this zine were:

· Ayça Atabey

· Colton Botta

· Harry Dyer

· Esther Priyadharshini

· Jen Ross

· Cara Wilson

Our thanks and appreciation to the teachers, pupils and support staff at the three schools that took part in this project.

Thank you to the artist-facilitators who led and co-led workshops: Lewis Wickwar, and Sarah Calmus, Tyler Carrigan and Kara Christine at ARTLINK.

Thanks to the other members of project team for their support and input: Judy Robertson, Jo Spiller, Laura Meagher, Craig Steele and the team at Digital Skills Education, Tina Livingston and Goodison Group in Scotland, and Dynamic Earth. Finally, huge thanks to Elspeth Maxwell of Dog and Fox, who designed this zine.

The authors are grateful to the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the Bridging AI Responsible Divides programme for research grant AH/Z505560/1.